- Based in Overtown Miami, FL

- info@nicolecrooks.com

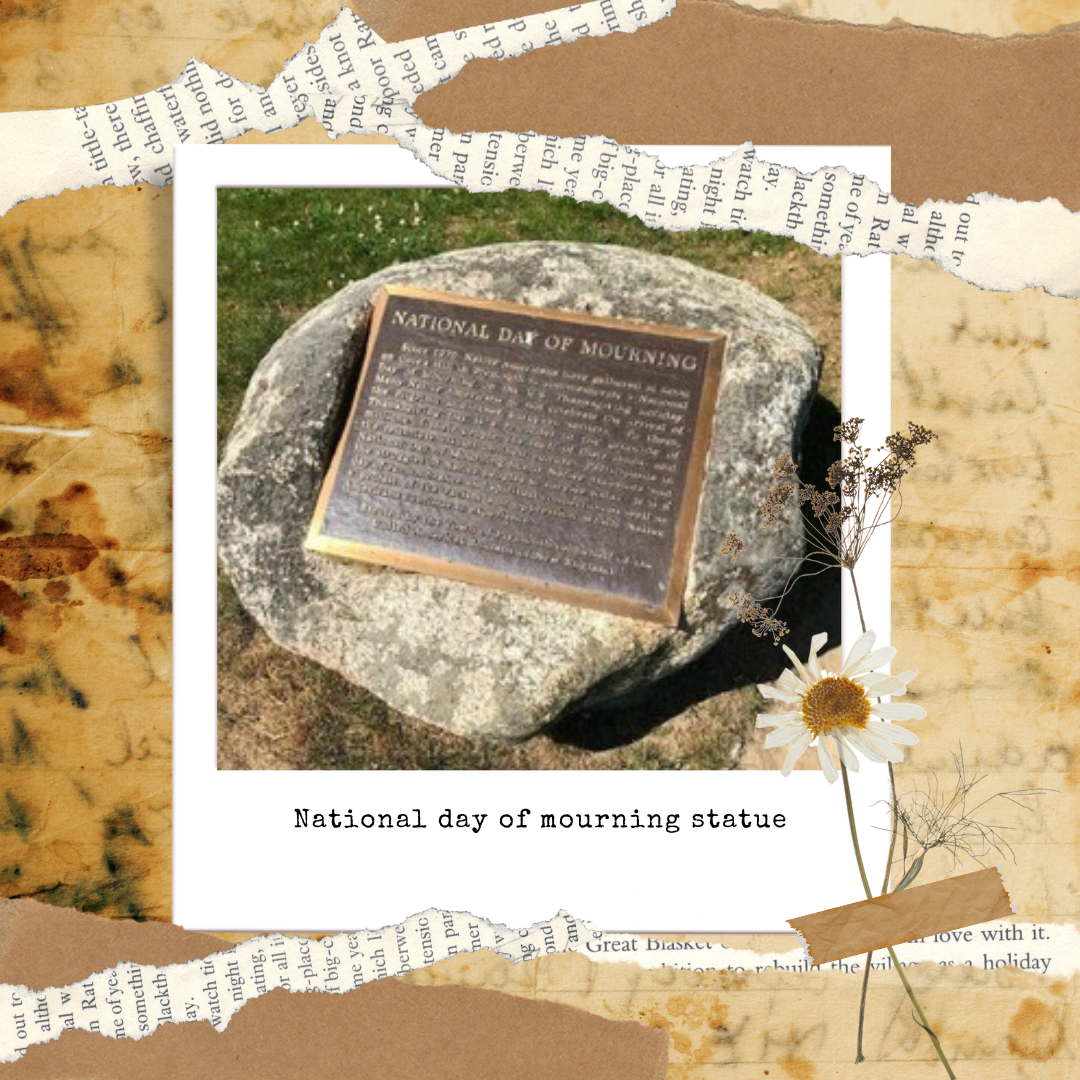

On both The National Day of Mourning–and Thanksgiving 2024

As a child, growing up in Amherst, Massachusetts, most Thanksgivings felt less like a holiday and more like an episode of Survivor– and for the record, I didn’t volunteer to participate. While my Wildwood Elementary classmates piled their plates with turkey, stuffing, and green bean casseroles, I was standing at Plymouth Rock with my mother and my Native “Aunties, Uncles, and cousins,” fasting and mourning. She called it “standing in solidarity.” I called it “being hungry, cold, miserable, and often wet.” (it almost always rained. It was almost like the sky was crying too).

The real pain, however, came afterward. I knew on Monday I’d have to endure the stories of my classmates’ bountiful “supper” tables of harvest—especially their excitement about their green bean casseroles and love for pumpkin pie, a dessert I never quite understood. Pumpkins, as far as I was concerned, were for decorating. Sweet potato pie, on the other hand? Now that was dessert. Aunt Aver’s sweet potato pie wasn’t just a pie—it was a blessing straight from heaven’s “Easy Oven” bakery as far as I was concerned.

When we got home, here came the dreaded phone calls to family in Macon and Peoria to let everyone know how much we loved, appreciated, and were grateful for the gift of them. Through the receiver, I could practically smell Aunt Aver’s collard greens, simmered with love, and Aunt Ver’s squash casserole, creamy, tasty, and buttery with a perfectly golden crunchy top.

“Lawd, Geneva,” someone would exclaim, “you know you stuck your toe in that potato salad”

“And Aver, knows she can cook” another voice would add, “those greens! Chile, you sho nuff put your whole foot in them.”

As a child, I found these descriptions both a bit amusing and very concerning. But mostly, if I wasn’t there, I was just mad. Why couldn’t I be there, eating and laughing with my family, instead of freezing and hungry in Massachusetts? Brother Malcolm was undoubtedly right!

Meanwhile, in a land far far away, my family was enjoying a feast so legendary it hurt to hear about. Aunt Ver’s squash casserole, Cousin Geneva’s potato salad, Grandma Nonie’s oyster dressing… whew, child! And don’t get me started on the greens…the pot liquor alone was, as my Cousin Corey would say… “ the nectar of the gods”.

Looking back, maybe it’s no surprise that I eventually moved to Miami. If I was going to stand in solidarity, at least I wouldn’t have to be cold while doing it.

As a child, I resented my mother’s insistence on fasting and mourning during Thanksgiving. Why couldn’t we have a “normal” holiday? Why did we have to make everything so serious? Why was she so very extra? I wanted to laugh, eat, and revel in the magic of my family. Oh how I love my family!

Yet as I grew older, I began to understand what my mother was trying to instill in me. Those mornings at Plymouth Rock weren’t about deprivation; they were about remembrance. She wanted me to know the truth behind Thanksgiving—the land stolen from Indigenous peoples, the labor stolen from enslaved Africans, the lives stolen in the name of abundance–predatory capitalism. She wanted me to understand that real gratitude requires reckoning, and reckoning requires a complete view and understanding of truth.

At the heart of that truth for me is my great-great-great-grandmother Amanda “Mandy” Clark Bowman. A beautifully powerful and spiritually abundant African woman. Grandma Mandy was what some might call a “house slave.” She cooked, cleaned, and took care of the needs of the family that enslaved her. She was also a midwife, a woman whose heart and hands carried the wisdom & power to usher life into the world, guiding mothers and babies through sacred and transformative moments.

Grandma Mandy’s hands probably prepared many feasts neither she nor her children could ever enjoy. I often wonder: What was she thinking as she labored in that kitchen? How did she reckon with the abuse her daughter, my great-great-grandmother Margaret, endured at the hands of the “woman of the house” who disdained every part of this “light skinned child”?

Her story is one of profound contradiction but also one of transformation. Grandma Mandy’s hands didn’t just labor—they created; they birthed and nourished. What she made out of necessity became a legacy of love and care, passed down through generations to Aunt Aver’s table in Macon. The collard greens, the cornbread, Grandma Mattie’s black eyed pea bread, Aunt Ver’s squash casserole—they’re more than food. They’re love turned into soul food & sustenance.

But let’s not forget that Thanksgiving isn’t just about my family’s story. It’s also about the unrelenting power and purpose of our Indigenous kinfolks. In spite of centuries of violence, forced displacement, and deliberate attempts to erase their cultures, they have survived, and prayerfully will continue to thrive with resilience and brilliance. Their teachings remind us that the land is alive, that it holds memory, and that it thrives when cared for with reciprocity and respect.

Our Indigenous siblings embody radical spirituality & purpose—to protect the land, preserve their cultures against all odds, and teach the world what it means to live in relationship with all living beings. Their connection to the earth is a model of care and reciprocity that we all would do well to honor and learn from.

My mother’s insistence on mourning at Plymouth Rock was her way of teaching me that the land we stand on isn’t ours to own and dominate—it’s ours to cherish and share. Both Indigenous and African traditions teach us that care for the land is inseparable from care for the people and all our relations. Returning the land to its rightful caretakers isn’t just an act of justice—it’s an act of healing, for the earth and for ourselves–it’s radical self-preservation.

Books like My Grandmother’s Hands by Resmaa Menakem remind us that trauma lives in our bodies, passed down through generations. But they also teach that healing is possible when we reconnect—to our ancestors’ wisdom, to each other, and to the sacredness of the earth. Grandma Mandy’s hands carried the weight of trauma, but they also carried the power to usher life, hope, well-being, and legacy into the future—through her love and sacrifices she created me. I am deeply humbled and grateful by this reality. Her story reminds me that healing isn’t just survival—it’s transformation.

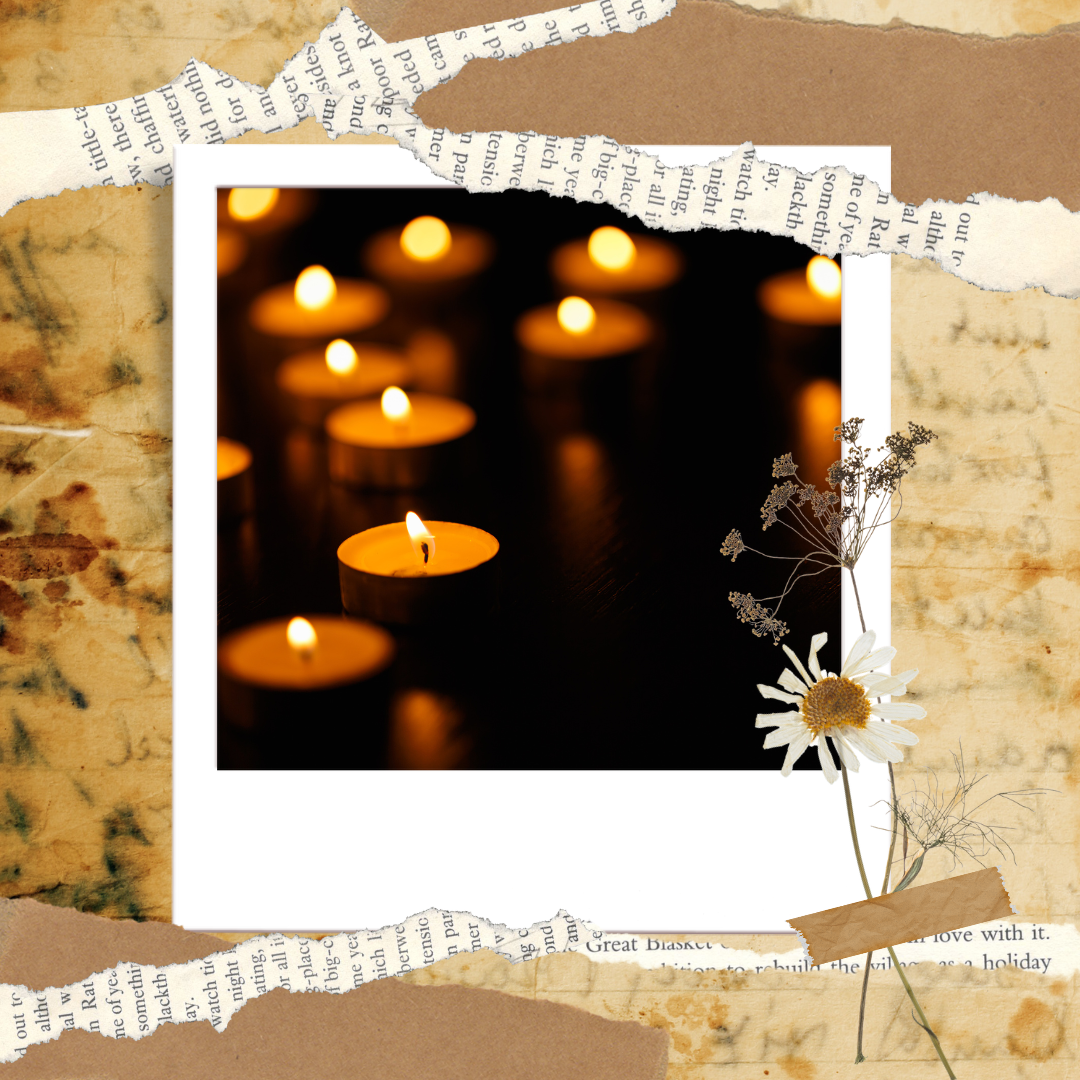

This Thanksgiving, I light a candle for our Creator. I light a candle for Grandma Mandy and all of my ancestors, whose hands birthed both life, love, and hope. I light a candle for my family, whose legacy of love, healing, and connection will endure forever, I light a candle for my beautiful and brilliant mother, whose lessons I only now am beginning to fully understand. I light another for my Indigenous family, whose care for the land, deep and abiding depth & connection to spirit, and embodiment of communal reverence teach us how to live in reciprocity. I light a candle for our children and all who will come after us. And I light one more candle for the transformation we are all capable of—for the healing that happens when we return to love, care, and humanity.

What if Thanksgiving became a day of returning? Returning to the truths of history. Returning the land to those who can steward it with wisdom and care. Returning to the African and Indigenous traditions that teach us to nurture all our relations—not just people, also the earth, the water, the air, and all living beings.

Needless to say, my relationship with this day is very complicated–especially as I work to navigate the discomfort. My children long for the celebration of joy, food, gratitude and Thanksgiving with friends and family. Honestly, so do I. Yet, the gnawing of the grief rooted in the truth is so deeply intertwined in my beingness that the best I can do is rest in the dichotomy. Gratitude, I’ve learned, isn’t about avoiding discomfort. It’s about holding it, with all its pain and beauty. It’s about remembering Grandma Mandy’s hands as they turned labor into love and scraps into sustainability. It’s about honoring the land, not as a possession but as a sacred partner in our shared survival. It’s about remembering that everything I do or don’t do in each moment has the power to heal the seven generations that have come before me and the seven generations yet to come. Above all else, it’s about choosing love, humanity, and healing–over, and over, and over again.

This Thanksgiving, I return to Grandma Mandy’s hands, to the memories of Aunt Ver’s squash casserole, to Aunt Aver’s delectable greens, pies, (really everything she cooked) and to the warmth and magic of our 755 Legacy Village in Macon. I return to the truth that abundance is not in what we take but in how we love, what we value, and who we care for.

May we all return—to the land, to the lessons of our ancestors, and to the transformative power of love, healing, humanity, and care– of and for each other. Always.

Comments are closed